By

Dr Graham Little PhD AFNZIM

January 2004

Content

Abstract

Understanding of a person remains confused and debated; in psychology the

manner and type of cognitions are seen and understood to influence the person,

whereas in psychiatry, all that is human is taken as a medical condition.

Frequently these two quite distinct ways of seeing and understanding people

seem to operate and act and react within quite different worlds, one often

ignoring or demeaning the other professionally, ethically and legally.

This paper outlines a model of causality

of human mood and conduct that offers complete reconciliation of these two

views of people.

The paper discusses how the model leads to the phenomenological insight

that the tension between physical causation and free will is a core and

fundamental facet of the human experience; necessarily and unavoidably experienced

by all people. Our humanity is forged in this effort of mind to overcome

matter, all freedom rooted in the struggle to free the will in the mind

of the individual to surmount the drives and causal forces within the body

and brain of that same person.

The paper clearly defines this conflict of free will and cause, showing

how it arises within the model and is a necessary and fundamental aspect

of all human experience.

The causal model of human

mood and conduct 1

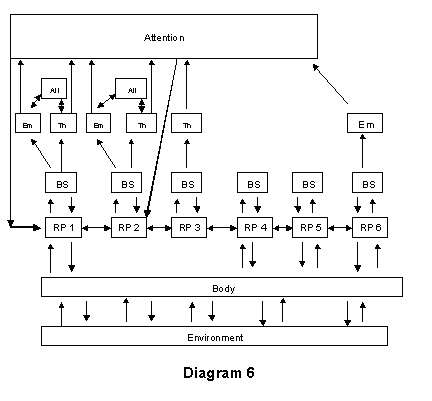

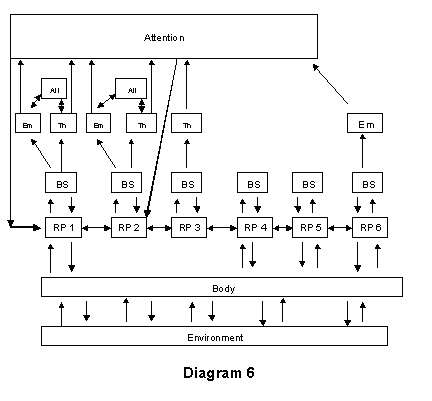

The theory is summed in the diagram below. The diagram is precisely a diagram

of immediate effects as derived from the system PersonçèEnvironment.

The terms are defined as follows

Key points relating to the theory are as follows.

Relationship

between roles and mental sets

The idea of mental set, of systems of emotion and thought linked with a situation

or an object of thought, or some part of that system, is the basic structure

of personality. Variations in both structure and content of mental sets between

individuals explain differences in the personality of those individuals. However,

mental sets are not always readily identifiable by the person, most often they

can be, but could take considerable time and guidance requiring reflection and

exploring of history before the structures emerge.

It is useful to use a grouping of mental

sets, typically related to some situation or type of situation, this grouping

I call a role and matches the typical use of the term in the literature. A role

is defined as a set of behaviours and feelings related to some situation. So

roles would include father, mother, friend, lover, manager, coach etc.

If personality describes the overall structure and content of the mental sets

of a person that is personality is a term grouping all mental sets, then a role

describes the sub-groupings relative to a type of situation.

Roles are useful tools for assisting people to explore and best make sense of

what they do. For example, Eric Berne’s transactional analysis is based on roles

of parent, adult and child. In this system the concept is taken further, and

based on a more structured and fundamental theory of psychology.

Roles may be explored and used in two ways. First, by looking at how a person

typically acts in a situation, this explores their role structure in that situation.

It may then be useful to explore deeper and uncover why they feel that way,

and what in their history has resulted in the mental sets that underlie the

role. In this way roles can be explored in a personal development manner, highlighting

thoughts, attitudes and emotions that are helpful and those not so helpful,

enabling change of the role or removing role confusion, or they are used as

the start point for much deeper exploring of the person’s history and hence

their psyche.

The second way of using roles is as training tool. Situations are identified,

desirable outcomes agreed then the competencies and skills, attitudes and thoughts

that best enable the outcomes are identified and offered to the person. Emotions

need to be discussed, and the person needs to understand the emotional tone

important for the effective enacting of the role. But quite likely the emotions

will not initially be felt by the person, but emerge as the person builds fluency

with the role and those aspects of thought and action that constitute delivery

of the role. Building and consolidating roles is not only an important therapeutic

tool, but also an important aspect of personal growth, and an important aspect

of development in business and other professions.

Emergence

and importance of meaning

Elsewhere I have discussed how ideas arise4

, and how they emerge from an often-broad activity, not localized, necessarily,

although the verbal description may be localized, but this is not the fullness

of the idea, merely its verbal summary or notation or description.

The important issue is that the meaning of the idea cannot as a matter of principle

be assessed or in any way determined from the outside, meaning emerges only

from within, only the person knows the meaning, and in particular only the person

knows the meaning for them, for only they are able to relate and otherwise interpret

the idea in relation to their world view. It is the meaning for them the person

will act upon.

In more precise terms, meaning will typically involve the combination of several

mental sets, these being the sets most related to and most engaged with the

circumstances within which the individual is located. This does mean that a

person with significant diversity in their world view may act differently in

this situation than might be expected from their conduct in other, not immediately

related circumstances that will involve other, not immediately related mental

sets. Such circumstances will depend on the extent the person has an integrated

world view, the extent their personality is a ‘blended whole’ with most aspects

of their world view and emotional structures congruent one with the other. Where

this is not the case, and where mental sets are allowed to operate independently,

then the person may produce significant surprises.

There will also be meaning within meaning, within… The person may or may not

understand or be able to describe all the nuances, or underlying issues that

might be integrated into their ‘meaning’. This arises if or when the cognitive

aspect of some mental set has been lost, so only the feeling and the nuances

remain, but these can be very powerful feelings that provide the overall flavor

to the meaning.

The fundamental human phenomenological

condition: the struggle to be free

One of the major issues in any proposed general theory of psychology is the

question of cause: is physical causation a factor in human affairs, how, and

in what manner does it relate to or interact with free will?

Within the model as proposed, physical causation is the functioning of the body

in the form of the brain and central nervous system. The first and most simple

example is habit, which is explained as the brain and CNS operating without

active intervention of the mechanisms of attention, and the system functioning

as a fully physical system. Simple examples in life might be walking on a beach

while conversing with a friend, the mechanisms of walking left to habit, but

should matters change, such as the ground become rocky or uneven, attention

can be used to exercise control to ensure one does not trip; another example,

when driving a well traveled route, and failing to take the turn off wanted

due lack of attention with habit directing the vehicle to the regular destination.

These are all every day events where physical causation shaped conduct, or some

aspect of conduct.

The attention system in the model has two primary characteristics, first it

is able to be spread or focused, so attention can be interacting with many of

the operative systems or with only a few. Second, the manner of the interaction

of attention with some mental set can vary from passive to full active intervention,

so when walking on the beach, we can observe our action of walking, or we can

intervene and deliberately place our feet where we choose. In circumstances

where the attention system is not able to interact with a neural system, such

as might be with the autonomous nervous system, then we are not able to exercise

control, or otherwise influence the system and it is fully dominated by physical

causation.

The first point is that all mental sets are driven by physical causation, so

that in circumstances where a set is triggered, say by being in the appropriate

circumstances, then the emergence of our historical understanding and feeling

of such circumstances will occur, this is the borrowed knowledge of Ashby, arising

from memory, with the addition of the feelings and emotions encoded in combination

with that knowledge and memory of the circumstances. In short, in the first

instance, our reactions are due physical causation.

The second point is that where attention interacts with a mental set, and the

model has it that all aspects of our psychology are so able to interact, then

the attention system is able to mediate, modify, and even stop the physical

causation so that the affects of the mental set, while felt and or sensed within,

may not be evident from without. This is the exercise of free will: But seldom

is it exercised without a price in effort and energy.

Thinking

as an active event

Where physical causation is dominant there can and will be thoughts in association

with some events and feelings, this is the activation of the mental sets of

the model. However, these thoughts arise solely from memory, there are fully

and entirely ‘borrowed knowledge’, in that they are the thoughts (and the feelings)

we acquired from our previous experience and reflection upon such events.

In that these thoughts and feelings are historical, they represent historical

intent that is the historical manner we thought and felt of the events;

where this is still valid, and in particular where this is valid and the events

sufficiently the same, then this historical intent may be valid. However, where

events are changed, or where our views have developed, for example, where education

has altered our world view, then historical intent may not be valid, and it

is only by active intervention of attention that we can assess and re-assess,

and so exercise our current intent, that is to control the

physical causation, and to act in a manner we decide according to our choices

and free will.

This analysis is general, and in the absence of active attention moderating

a mental set, and re-assessing our options, then the mental set will be driven

by physical causation, and even though we will have thoughts and this can offer

the appearance of free will, in fact it is not, and we are acting out what are

in effect complex and sophisticated habits involving emotions and cognitions.

For much of life, in understood and slow changing circumstances, this is a benefit,

since energy is conserved, and life and existence has a comfortable flow. Such

circumstances are commonly called ‘being in one’s comfort zone’.

The danger of such comfort zones, as well as there advantages is well illustrated

in the example of driving a regular and well known route, coming to the intersection,

and thinking ‘have I been over the old bridge’. This means that the act of driving

was fully physical causation, and provided the circumstances were exactly as

they were last time the route was driven, it is not a problem; however, if on

the blind bend there was a major slip, or the bridge was washed out, or another

vehicle was traveling too fast on the wrong side of the road, then reaction

to the changed events would be increased by the time it took us to ‘attend’.

This is precisely lack of attention, as well understood, and having precisely

the effects as commonly expected. This is an obvious example; equally we can

have lack of attention to our partner, work, schooling, etc,

occurring over longer periods of time and with similar effects.

Effort of will

The imagery is one of cause in conflict with free will, this is not always the

case, and as outlined above, for much life, cause and free will are congruent

in our comfort zones where we do not have to exercise the effort.

The conflict of free will and cause comes most sharply in circumstances that

are difficult or stressful; for example, in the case of a marriage breakdown

and divorce, with children and custody and assets all being debated in addition

to resolving the blame and fear and uncertainty of the future.

The forces of physical causation within us, in events as demanding as divorce,

may easily press us to emotive and angry reactions not appropriate or not really

what we mean or intend toward the other person: we may say things we do not

really mean, we may do things we immediately regret, we may experience emotions

beyond that we have felt or normally feel. Containing these more extremes of

our mental sets, or our own causation may demand a most intense act of will.

The only technique is to hold reaction in check, and to ensure we move with

a slow deliberateness fully attending all we do and say. To act with such control

is extremely difficult, requiring considerable skill and more importantly a

deeper desire to do so. By this ‘deeper desire’, is meant that if the images

of self that surround and support the overall structure of self within the system

that is diagram 6 do not reflect this desire to self-control and composure,

then it is very much less likely that the necessary self control will be effectively

exercised. This ‘deeper desire’ is not ‘deeper’ in terms of the model, merely

that it is much less likely to ever be discussed, it may or may not be readily

apparent to the person themselves, who may not be immediately conscious of there

own self-image’, the system merely makes it clear there will be one, and it

will be influential, as are all the multi-faceted aspects of the self within

a person.

Collusion of our psychic self with causation

There exists an overall ‘self’; this includes everything that is ‘us’, mind/spirit,

the actual structure of self, and body. Within this model, there are several

components, for example, aspects of self, relating to self-image, other aspects

relating to our spirit, and others describing our body and operation of our

neural systems. The model also makes clear there is no reason to assume these

components are always operating in harmony, so we can be in conflict with ourselves,

the simplest example is where physical causation operates through our mental

sets pressing some particular reaction that we know will be counter productive,

yet we may struggle to contain.

Overall I propose that the psychic self (self, and mind and spirit, all aspects

of our psychic self, yet all embraced and able to be analyzed by way of the

model diagram 6) can be discussed and understood as separate from the physical

self, and that our physical self (psychological embodied in our mental sets

that bring historical intent to the circumstances via our borrowed knowledge)

can and is often in conflict with our psychic self. The exercise of free will

is when our psychic self dominates our existence and our conduct as regards

events, and physical cause or our physical self (causation) dominates our existence

when we do not exercise free will as regards our conduct toward events.

At all times, our attention systems are able to intervene,

and as a result able to moderate and able to facilitate the exercise of free

will and choice. Where the free will is not exercised, then I describe the circumstance

as one of collusion between our psychic self and physical self.

We choose not to intervene, whether that choice deliberate

or passive, we allow causation to operate, and often we know we have done so.

This position brings significant issues of motivation to the fore; for example,

in one mental set, I may want something, wish for it, but not willing to actually

do it. Then one day, events transpire whereby it will occur all one need do

is be passive. Say for example, it is a terrible event, such as the death of

a spouse, and he or she is caught swimming in a rip, the person looks on and

later pleads helplessness, and the event wanted, the death, occurred. The wish

for the death may never have been said, may never have even been fully admitted

by the person to themselves, but it was there. The deeper desire needs no more

elaborate explanation than available in diagram 6. Many aspects of many mental

sets will be only known to the person. Many other aspects of mental sets will

moderate the more extreme feelings and wishes, some of the wishes may not be

fully expressed as ideas, merely vague and broad sense of things preferred,

mental sets without full cognitive structures, perhaps drawing vague cognitive

definition from other associated mental sets.

The type of example outlined above can

be made as subtle or as complex as can be imagined, the analysis requires no

more than application of diagram 6 in order to facilitate insight and understanding,

our collusion may not be a deliberate or directly conscious act, merely a vague

resistance to taking any action, and where there may be restrictions to our

action, then we may even feel vindicated in our lack of action: Well able to

rationalize. Where we remain in touch with broader and less public aspects of

our psychic self, then most likely we will know and have some if not guilt then

disquiet knowledge of our collusion. The depth (in terms of not available to

public review, or even not fully conceptualized by the person themselves) of

this structure leaves forever the potential for anyone to surprise and to exhibit

conduct quite unexpected from all previous conduct.

In any and all circumstances where causation dominates free will, then we are

either inattentive, or we allowed it to occur (we colluded with cause), or we

were unable to stop it.

Cause beyond our control

There are two circumstances where free will is not able to dominate cause: first,

when events are beyond that any person could be reasonably expected to contain.

For example, under torture or threat to life, it is not expected a person exercise

full psychic control; or when a father sees their daughter being raped, immediate

reactions overpowering psychic control would be expected. Generally, in daily

life, any lapses in exercise of free will become the responsibility of the person

with little other consequence. The issue comes more to the fore when the resulting

conduct was illegal, then any mitigation becomes very important, as does the

judgment of ‘circumstances beyond those a normal person would be expected to

tolerate’, this judgment is social, cultural and moral, and as such moves beyond

the bounds of a general theory of psychology and what it can and cannot tell

us, for the judgment requires selection of values of variables, and as such

goes beyond the nature and operation of the variables themselves.

The second circumstance is where the attention mechanism is unable to cope,

in particular being defective. It needs be clear that the attention mechanism

cannot, as a matter of principle, be defective for any reason of psychology:

The model allows no such disorder. The only manner of defect of the attention

system is where the mechanism of attention is defective that is the attention

system is defective due neurological disorder. As discussed and defined, all

such neurological disorder is described as mental illness. Therefore, where

a person is mentally ill, then they cannot exercise nor can they be expected

to exercise free will in the manner and to the extent expected of someone who

is not mentally ill. This paper is on psychology, and psychological dysfunction,

and will not discuss or explore issues defined as mental illness, which are

not psychological but neurological.

Cause and our

energy

The model and implications raise various questions:

As stated in the discussion of the model,

only attention is able to intervene such as to thwart or otherwise modify the

neural operation according to the inherent mechanisms of the neural system.

The inherent mechanisms are that defined and described by the brain structures.

We can understand the manner of attention intervening in a mental set as exactly

equivalent to being able to move one’s left arm, we know internal states, and

by activating one of those states then we achieve certain bodily outcomes. Attending

to and moderating one’s internal psychological states is exactly the same, but

not a process deliberately taught, nor emphasized as significant 5.

The model of neural functioning has been previously outlined6

, and requires no more than already well understood and accepted. To follow

the argument, a mental set determined by causality with neurons following the

path of lowest energy barrier, this being in large part determined by previous

use and repetition. This is effectively the definition of habit.

The path of lowest energy barrier will be influenced by other factors, for instance:

The balance of neural flow will be along

the path of least resistance, with entropy determining that the energy will

dissipate to fill all available states of lowest energy. There will be a minimum

difference between energy barriers that will act as a complete deterrent, below

this difference, the energy may well spread itself through several mental sets,

but only those in some way interrelated to and interactive with those currently

operative. To that extent, a mental set can also be seen as bounds within which

neural energy is contained, this energy also able to be called our ‘psychic

energy’, particularly as regards those mental sets that do underpin our personality

and spirit.

Two fundamental types of psychological

neural mechanism

The model contains two quite different types of psychological component, Thought

and Emotion. From the typical experience of people, there are two quite distinct

circumstances where cause and free will collide.

a. Where the overall emotional state is ‘normal’, that is the overall level of energy is relatively low, then the difference between one route and another may be small, and the effort required to redirect the energy flow quite modest, so that then the mental set is determined by free will and ‘what I want’ as opposed to habit and cause. For example, a brainstorming session generates energy and re-directs energy into links that would not occur by way of cause alone. Here, non-preferred pathways are being adopted as a result of us expending energy into the task of finding new links for some ideas. Increasing the level of energy makes pathways that would not be preferred into potential options with the amount of energy available to the system being sufficient to overcome the energy barrier.

Part of the distinction between these

two psychological states may be due to activation of sensitised neurons, generally

increasing the level of energy in the system. However, this does not alone offer

explanation for the psychological fact that if we are rational and seeking new

ideas, then the gentle level of energy of brainstorming will often succeed,

whereas in some agitated state, the effort of containing emotional reactions

can be quite enormous, at times making us wonder if we can cope at all.

What emerges is the view that our emotions are a far greater driver of energy

that our cognitions, and where we are struggling to cope with cognitions, then

the core of our struggle is to understand and contain the emotions driving our

cognitions.

Understanding emotions

In the following questions and answers I have tried to address various issues

arising from the model.

| How do different emotions arise? |

The proposal is

that emotions are physically based; therefore they emotions must have

various chemical equivalents in the brain and CNS. This does not mean

that the exact same chemical has the exact same affect in every person,

although there is likely a range of emotions a chemical will generate,

and beyond this other chemicals are affective. Also, it is very possible

that the same chemical can induce variations of mood depending on the

amount released, and the cognitions accompanying the release. Finally,

it is also possible that combinations of chemicals result produce a

mood, and by altering the combinations, then many variations become

possible, again all associated with cognitions. These blends, and consistency

of these blends across mental sets account for the emotive part of attitudes,

even permeating the whole worldview, so a person is ‘fearful’, ‘optimistic’,

‘pessimistic’, ‘antagonistic’, etc. The person may not see himself or

herself this way, but others do; they may not register their state as

‘pessimistic’, yet all their worldview may be influenced by the chemical

blend that produces this feeling, for them it is ’normal’ state, and

likely they think everyone feels so. To express themselves as ‘pessimistic’

about something will involve additional levels of the chemical blend

and significantly heightened emotional experience from that they regard

‘normal’. |

| How do we know what is a proper emotion

under some given circumstances? |

Depending upon the circumstances,

there may be generic mood generation, for example flight or flee response,

on smiling and laughing, with someone nearly slipping in non-threatening

circumstances, or some degree of solemnity upon meeting new people.

Beyond such common and basic circumstances, then the emotions related

to circumstance is a cultural phenomenon and is not explicable under

this model, which can only state which is and suggest which is likely

not cultural. Note: that all details of emotions tied to cognition tied

to events describes values of variables of the model, and as such is

beyond the model itself, any suggested genetic implications only arise

as result of the universality of the reaction. |

| How do emotions ‘build up’ over time? |

With emotions chemically based

and our psychic energy contained in mental sets, then if a mental set

is repeated, and there is no resolution, no release of any issues, then

there it is within the scope of the model to propose such chemicals

can build up within the mental set, that is a physical build up, only

resolved by some form of release of the chemicals and that by some form

of completion of the mental set and that implied. It is then possible

at some point for the build up to be too strong, and for our containment

to fail, so the emotions ‘boil over’. |

| How and why do we feel righteous and feel

that some reaction is ‘me’? |

If for example, there is an urge to react in some manner, that urge will be causality at work, and we feel the urge resulting from the mental set systems seeking to proceed to their final resolution in outputs; and say our self-image is consistent with the outcomes and outputs of the urge. Then we will have feelings that this is me, it is how I feel and how I want to act. However, the outputs from the mental set may or may not be the most effective, for example, if it required beating a person near to death. |

| Why is it that in some rage ideas that

you know before and after are wrong can seem so right at that moment? |

Emotions are a greater driver

of mental sets that thought, so that when sensitised neurons triggered,

and serious emotions result, then the cognitions that best fit and suit

those emotions are likely to be triggered. It is essential to remember

that emotions cannot create cognitions, merely reinforce those that

currently exist. Rationally we may think this way; and ignore or otherwise

contain ideas that are extreme or unacceptable for moral or legal reasons.

When some emotions triggered, then the mental set associated may quite

overcome all else, and this will be especially true if self-image supports

the outputs of the mental set, and when or if we truly would like or

wish for the outputs from the mental set. See the discussion on collusion

of cause and psychic self. |

| What are deeper feelings? |

The model proposes there are

no ‘deeper’ feelings in the sense of truly below some other feelings.

They are all at the same level, but they are not all accessible to the

same degree, nor are they all as definite or as well supported by cognitions

that give sharpness to the emotions. So, some we may wish for something,

hardly daring to acknowledge it to ourselves, and never admitting it

to another. We may not even think about it too hard, and it may not

be completely clear what it is we wish for. It is not fully articulate,

not fully expressed even to ourselves, merely a vague desire that would

only crystallize if fate enabled it for us. Such might be a ‘deeper

feeling’. The idea of deeper feelings comes forth also in relationships,

but again, it is not ‘depth’, rather it is breadth, the extent feelings

are shared, and intensity, such that it is love, and not something more

superficial, such as companionship or affection. Each of these emotions,

love and affection, will involve different chemicals and chemical blends

within the person, these intertwined with actions and moods that reinforce

the idea of love, and this itself reinforced and supported by insight

and understanding of the other person that can only come with trust

and openness and time. |

| Is there a true self? |

There are at least three definite

facets of self: first, there is our self-image, that is images of how

we see ourselves, there is also thoughts about our selves, these being

some blend of positive and negative, supporting and self-defeating.

Second, there is what we might say about ourselves to another, and this

may bear no relation to the actual structures about our self. Finally,

there is how we conduct ourselves, and how others would see us. These

aspects of self may or may not be congruent. Each of these is ‘true’;

sayings such as ‘know thyself’, or ‘to self be true’, relate to working

to make the aspects of self congruent, and that being true to self is

avoiding too hasty decision, and ensuring that what is agreed is what

is felt in one’s heart, which itself means it has had time to be integrated

into all relevant mental sets, and it sits easily both in terms of what

I think, and it in terms of how I feel about it. |

| What is ‘instinct’ within this structure? |

First, the body knows and

has noted more than the mind sees, and as that comes forth then is instinct.

Bringing to the fore all of what we know, both mind and body, requires

we quiet the haste to fill the space. Cause will result in any quietness

in our minds; any space, being filled, and this activity will overpower

any emergent insights coming from what we, in the form of our bodies

and brains, might have seen or know, without our mind/consciousness

having registered we know. |

Summary of cause and free will